joshya/Fotolia

joshya/Fotolia

Last weekend, on our way through upstate New York to get a Christmas tree, my teenagers and I stopped in a small, claustrophobic dog shelter.

“Stopping by” dog shelters impulsively often results in new dogs, so it is ill-advised.

Inside a cramped space smaller than my living room, clearly stressed and likely neurotic, large dogs were throwing themselves against the gates of their kennels. Like free runners they ran up the concrete walls, propelled themselves against the gate with a crash, back to the ground and back up the wall again.

It was loud — really loud — with growling and barking and cage smashing.

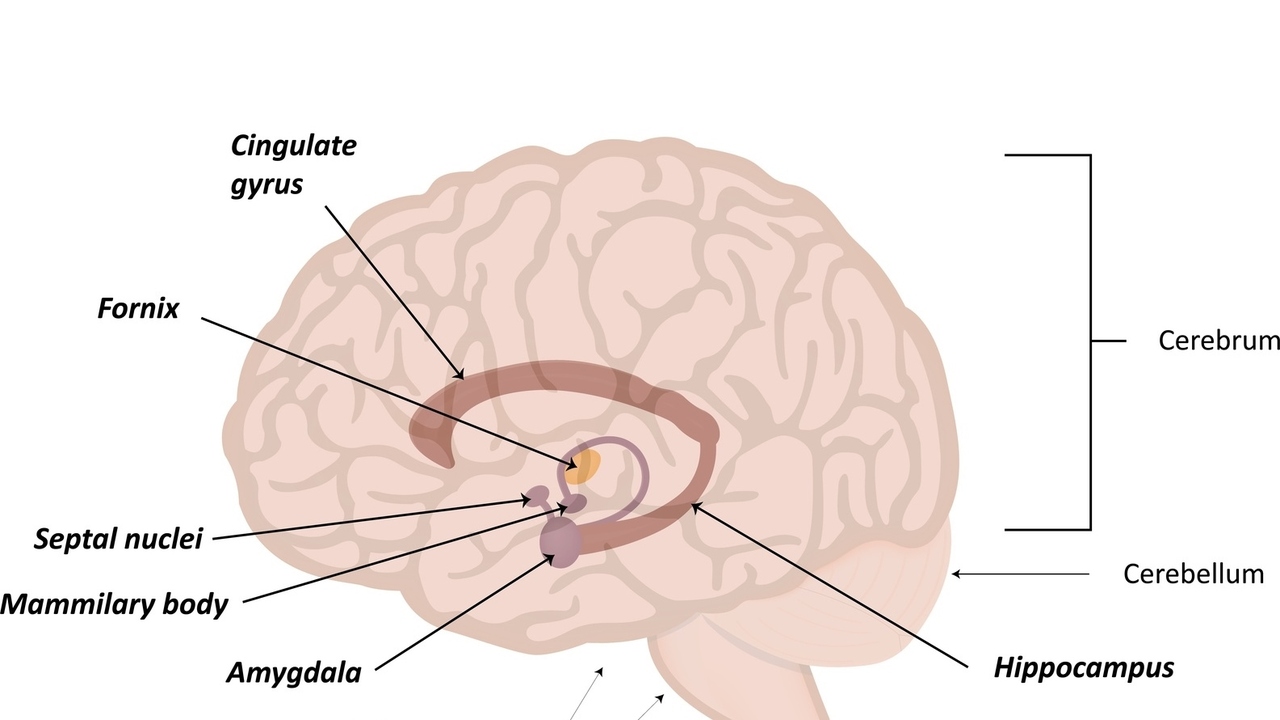

I have three dogs, even at one time had four. But here’s what happened: the sound and sight of these dogs set my limbic system, the part of the brain that controls emotions and behavior, on fire.

This environmental stressor signaled “danger!” and the cue was sent to my amygdala, which sent out the “fight or flight” response. The amygdala, Greek for “almond,” is a similarly shaped region that controls emotion, especially fear.

The “fight or flight” response is a sequence of internal processes that protects us in a dangerous situation, preparing our bodies for struggle or escape. (4)

My ventromedial prefrontal cortex or vmPFC, the higher level thinking place in the brain, received the message, and performed crisis management. I could then observe, “The cages are locked. The dogs are just excited by visitors. Even in the unlikely chance one of them breaks out, nothing is likely to happen. I like dogs.” (1)

My hippocampus, the part of the brain that forms and stores new memories, joined in and I was reminded of my fond experiences growing up with large dogs (and the lollypop aggression of my diminutive Jack Russell).

All of this brain functioning enabled me to stay long enough for my daughter to fall in love with a brown dog named Samantha. I left calm, in one piece, and dog-free.

This is the normal response to an environmental stressor.

In people with post-traumatic stress disorder, there is a breakdown in communication between these regions in the brain, and therein lies the difficulty.

Brain imaging of people suffering from PTSD confirms three areas of involvement in the brain: the amygdala, the vmPFC and the hippocampus. (1)

Biologist Dr. Phil Newton wrote for Psychology Today:

“Brain imaging studies of PTSD sufferers generally show two things; reduced activity in the vmPFC and increased activity in the amygdala. A long-held interpretation of these studies is that, in PTSD, the vmPFC is asleep at the wheel, allowing the amygdala to go unchecked and thus produce many of the intense anxiety symptoms that are a key feature of PTSD.”

Essentially, the cool-as-a-cucumber hostage negotiator, the vmPFC, can’t do its job, and the amygdala is going off willy-nilly without restraint.

Let’s say a woman is mauled by a dog and suffers serious injuries. Years later, If she has PTSD and enters that same animal shelter, the aggression and excitement of the dogs will put her at the mercy of the terror her amygdala generates, without the benefit of the “higher thinking” and calming influence of the vmPFC.

She is instantly in “fight or flight” mode. The amydala is attached to the hippocampus, where long-term memory is stored. Her long-term memory immediately brings up her prior dog attack.

She may feel the same fear and horror, triggered by the environmental stressors of barking, excitable dogs, that she did the day she was attacked. She has a flashback of the traumatic incident, and she physiologically re-experiences the attack because the vmPFC is not doing its job. (3)

The exact interaction between the amygdala and vmPFC is still not understood. It's not known whether there is a back-and-forth between the amygdala and vmPFC, or perhaps the shutting down of one function does not necessarily increase the other but makes it more noticeable. (2)

Newton postulates other regions of the brain are likely involved. More study is necessary towards developing a science-based approach to treating PTSD.

For the worried dog lovers out there, I just checked with the dog shelter, and Samantha has been adopted.

Source:

1) The Anatomy of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. psychology today.com Retrieved December 14, 2015.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/mouse-man/200901/the-anatomy-posttraumatic-stress-disorder

2) Memory, Learning, and Emotion: the Hippocampus. psycheducation.org. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

http://psycheducation.org/brain-tours/memory-learning-and-emotion-the-hippocampus

3) Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder - Symptoms. WebMd.com. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

http://www.webmd.com/mental-health/tc/post-traumatic-stress-disorder--symptoms

4) Fight or Flight. psychcentral.com Retrieved December 14, 2015.

http://psychcentral.com/lib/fight-or-flight

Reviewed December 15, 2015

by Michele Blacksberg RN

Edited by Jody Smith

Add a CommentComments

There are no comments yet. Be the first one and get the conversation started!